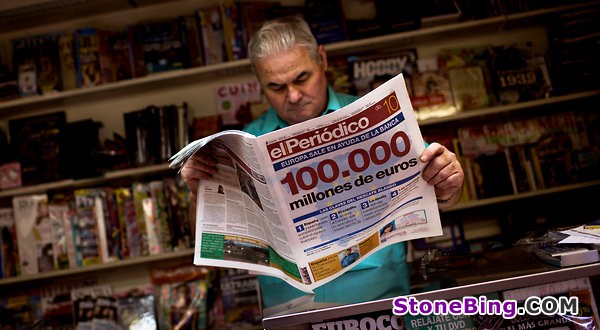

In Barcelona, a man read a newspaper announcing a bailout for Spanish banks.

LONDON — As Europe works to prop up Spain’s wobbling banks, its leaders still face a problem that plagues the Continent’s increasingly vulnerable financial institutions — a longstanding addiction to the borrowed money that provides the day-to-day financing they need to survive.

The weakness afflicts banking systems including that of Italy, whose fragile economy is even bigger than Spain’s and whose banks also rely heavily on borrowed money to get by. In Spain’s case, the flight of foreign money to safer harbors, combined with a portfolio of real estate loans that has deteriorated along with the economy, led to the collapse of Bankia, the mortgage lender whose failure set in motion the country’s current banking crisis.

Europe hopes that this latest bailout — worth up to 100 billion euros that will be distributed to Spain’s weakest banks via the government in the form of loans, adding to their long-term debt — can resolve the problem.

Financial markets were once again on edge, with analysts cautiously welcoming the stopgap development, while leery about whether the bailout would hurt or help Spain’s borrowing costs and whether the coming Greek elections would inflame the markets. In Japan and Hong Kong, markets were up around 2 percent early Monday.

“It’s another step in a long process,” Charles Kantor, a portfolio manager at Neuberger Berman in New York, said on Sunday.

“The Spanish banks, like the banks in France and Italy, all need capital.”

“The bigger question is whether Spain itself needs a bailout,” he added. “For now, though, the European patchwork approach of dealing with the issues is still working.”

Investors and analysts worry that highly indebted banks in other weak countries like Italy might face constraints similar to those of Spain in the months ahead.

Last month, the ratings agency Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the credit standing of 26 Italian banks, including two of the country’s largest, UniCredit and Intesa Sanpaolo. Moody’s warned that Italy’s most recent economic slump was creating more failed loans and making it very difficult for banks to replenish their coffers through short-term borrowing.

Because they have yet to experience a colossal real estate bust, Italian banks have long been viewed as healthier than their bailed-out counterparts in Ireland and Spain. And bankers in Italy were quick to argue in recent days that Italian banks should not be compared with those of Spain.

But as economic activity throughout the region came to a near halt, especially in perpetually growth-challenged Italy, the worry was that bad loans and a possible flight of deposits from that country would pose a new threat to banks that already were barely getting by on thin cushions of capital.

And Italian banks cannot avoid the stigma of the government’s own staggering debt load. Italy’s national debt is 120 percent of its gross domestic product, second only to Greece among euro zone countries.

Also hanging over Europe’s banks are the losses that would hit them if Greece were to leave the euro currency union, throwing most of their euro-denominated loans into a state of default. Banks in France and Germany would be hurt the most, as they have been longstanding lenders to Greece. In a recent analysis, Eric Dor, an expert in international finance at the Iéseg School of Management in Lille, France, calculated that French banks would lose 20 billion euros, and German banks 4.5 billion euros.

Crédit Agricole, for example, via its Greek subsidiary, has about 23 billion euros in Greek loans on its books. If Greece were to leave the euro, the losses could exceed 6 billion euros, analysts estimate.

Because it was the financial excesses of banks in Ireland, and now Spain, that forced their home countries to eventually seek bailouts, finding a Europewide solution to overseeing financial institutions has become a pressing priority for the euro zone’s leadership. Otherwise, Europe would be able to address the weaknesses of member country banks only when the time came to rescue them. The recent belabored negotiations by Brussels, Madrid and Frankfurt over how much help to give Spain and how to do it illustrated just how slow and difficult it would be to move toward a common European bank oversight system.

But as the president of the International Monetary Fund, Christine Lagarde, said on Friday in a speech in New York, there is little time to waste in this regard.

“European banks are at the epicenter of our current worries and naturally should be the priority for repair,” she said. Ms. Lagarde, who from her earliest days at the fund has focused on banking problems in Europe, left little doubt how the issue should be addressed. “Let me be clear,” she said in her speech. “The heart of European bank repair lies in Europe. That means more Europe, not less. Less Europe will be bad for the Continent and bad for the world. So, policy makers in Europe need to take further action now to put the monetary union on a sounder footing.”

At the root of the issue is a simple fact: just like the countries in which they operate, most European banks are highly leveraged entities. They are heavily dependent on borrowed money to operate day to day, whether making loans or paying interest to depositors.

For decades, the loans that European banks made to individuals, corporations and their own spendthrift governments far exceeded the deposits they were able to collect — the money that typically serves as a bank’s main source of ready funds. To plug this funding gap, which analysts estimate to be about 1.3 trillion euros, European banks borrowed heavily from foreign banks and money market funds. That is why European banks have an average loan-to-deposit ratio exceeding 110 percent — meaning that on any given day, they owe more money than they have on hand.

In Spain, the problem has been even more acute. Bankia, before it failed, had a loan-to-deposit ratio of 160 percent, one of the highest in Europe. Even the strongest banks in the country, like Santander, the global banking giant, have a fairly risky ratio of 115 percent, while big Italian banks like UniCredit rely on bulk borrowing to a similar or higher degree.

In the United States, the comparable figure is about 78 percent, which means the biggest American banks have a surplus of deposits and extra cash that they must put to work. (That can pose its own perils, as JPMorgan Chase recently demonstrated with its disastrous trading bets built on excess deposits and hedges against losses.)

Of late, Europe’s bank funding gap has been filled largely by the European Central Bank’s temporary program of cheap, three-year loans to European banks.

Italian and Spanish institutions were the most aggressive in lining up at this lending window, and they used much of the cheap financing to buy their own government’s bonds. In the long run, that particular form of patriotism is likely to hurt those banks’ finances if the value of the bonds continues to decline.

In a recent report on the Italian economy, analysts at Citigroup said they did not expect Italian banks to experience a fate similar to that of their Spanish counterparts anytime soon. But they did highlight disturbing trends in nonperforming loans in Italy, which have doubled since 2008.

And they warned that Italian banks’ buying of government bonds made them ever more vulnerable to the staggering debt of the government in Rome.